Remark

Please be aware that these lecture notes are accessible online in an ‘early access’ format. They are actively being developed, and certain sections will be further enriched to provide a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter.

2.2. Identifying Patterns of Missingness#

2.2.1. Identifying Missing Values#

In pandas, we can utilize the isna() or isnull() methods to identify missing values. Both methods function identically and can be used interchangeably to detect NaN (Not a Number) entries in the dataset.

2.2.2. Example: Mississippi River Gage Height Data#

To analyze the distribution of missing values over time for the Mississippi River at Thebes, IL dataset, focusing on the ‘77623_00065’ variable (which represents gage height):

The dataset for the Mississippi River at Thebes, IL was analyzed to examine the distribution of missing values in the gage height (ft) variable over time. The data was processed to ensure a complete 30-minute interval time series, allowing us to identify and visualize missing values effectively.

Data Ingestion and Cleaning: First, we isolate the timestamp and gage-height fields, standardize names, and enforce a unique, chronological index.

Eliminating duplicates ensures each timestamp corresponds to at most one measurement, avoiding artificial clustering or gaps.

Constructing a Continuous 30-Minute Time Base: To clearly identify missing observations, we generate every half-hour timestamp between the earliest and latest recorded times, then reindex.

This step turns absent timestamps into explicit NaN values in gage_height_ft, making gaps instantly visible and quantifiable.

Quantifying Overall Missingness: We compute both the raw count and the percentage of missing gage-height readings.

Total records: 17520

Missing measurements: 388 (2.21%)

Out of the complete half-hourly series, 388 values are missing, representing 2.21% of all time points.

Now, this dataset looks like the following.

2.2.3. Visualizing Missingness Patterns#

2.2.3.1. Heatmap of Missing Data#

A heatmap (can be found in seaborn library) displays each timestamp (x-axis) against the single variable (y-axis), highlighting missing points in red.

Dense red clusters indicate periods with extended data loss (e.g., sensor outages or transmission failures).

2.2.3.2. Temporal Scatter of Gaps#

Plotting each missing timestamp along the time axis clarifies whether missingness is random or concentrated.

Missing readings appear sporadic with occasional clusters—suggesting Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) for most periods, punctuated by brief outages.

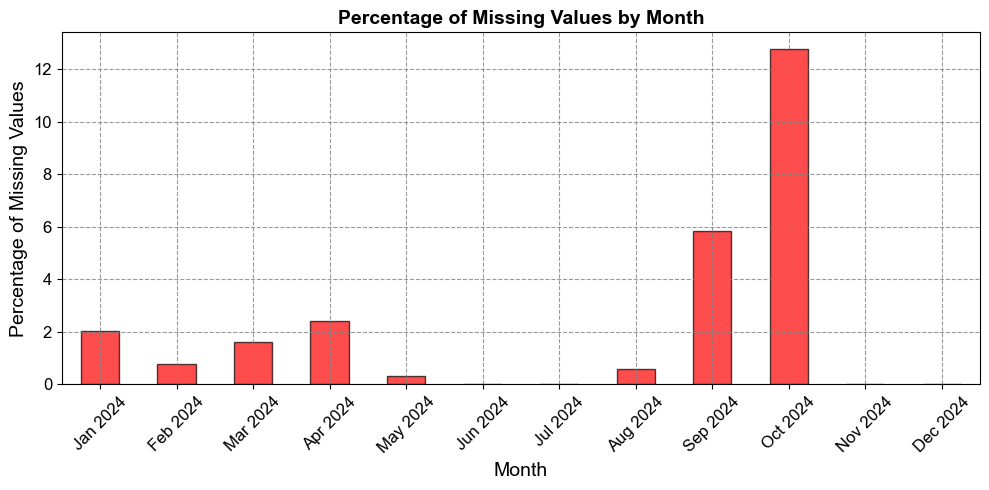

2.2.3.3. Monthly Missingness Bar Chart#

Aggregating by month highlights seasonal or operational trends in data availability.

This visualization highlights periods with higher concentrations of missing data.

Peaks in the bar chart may correspond to specific months with data collection or transmission issues.

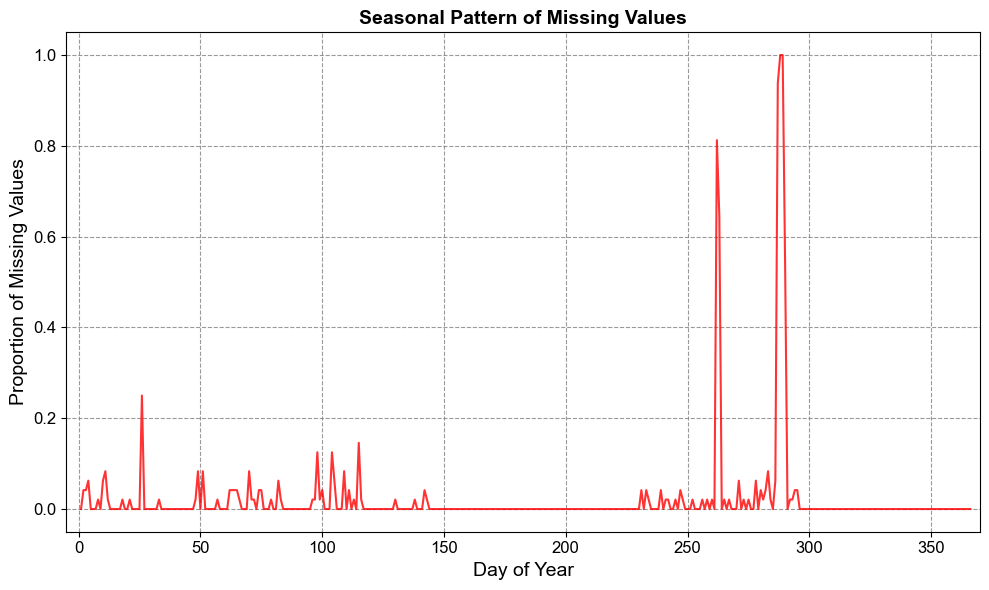

2.2.3.4. Day-of-Year Seasonal Profile#

By grouping missingness by day-of-year, we detect recurring annual patterns.

Seasonal patterns may emerge if certain times of the year consistently show more missing data.

This could be due to environmental factors (e.g., flooding or freezing affecting sensors).

2.2.4. Correlation Between Missingness and Recorded Values#

To determine if there is a relationship between recorded values and missingness, we analyze whether low or high gage height (ft) readings are more likely to precede or follow gaps:

Correlation between gage height and subsequent missingness: -0.04

Interpreting this result:

The correlation is very close to zero, suggesting there’s practically no linear relationship between the gage height and whether the next measurement will be missing.

The slight negative value (-0.01) might indicate a very weak tendency for higher gage heights to be followed by non-missing values, but this relationship is negligible given how close to zero the correlation is.

Remember that this correlation doesn’t imply causation, and given its near-zero value, it suggests that the gage height doesn’t have a meaningful impact on whether the subsequent measurement will be missing or not.

2.2.5. Little’s MCAR Test#

Little’s MCAR test [Little, 1988] is a multivariate statistical test that evaluates whether the overall missing data pattern across an entire dataset is consistent with the MCAR assumption. Unlike univariate approaches, it provides a comprehensive assessment by examining all variables simultaneously.

Methodology

Little’s MCAR test operates through a sophisticated statistical framework:

Expectation-Maximization (EM) Algorithm: Estimates population parameters (means, covariances) under the MCAR assumption

Pattern-Based Analysis: Identifies all unique missing data patterns in the dataset

Mean Comparison: Compares observed group means for each pattern with EM-estimated expected means

Chi-Square Statistic: Calculates test statistic based on these mean differences across patterns

Hypothesis Testing: Tests H₀: All missing data in the dataset is MCAR

2.2.5.1. Example: Weather Time Series Analysis#

Consider a temperature monitoring dataset with missing readings and categorical weather conditions:

Sample Time Series Data:

| Temperature | Humidity | Weather_Condition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2024-01-01 | 22.0 | 70 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-02 | 23.0 | 72 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-03 | NaN | 75 | Cloudy |

| 2024-01-04 | 25.0 | 68 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-05 | 24.0 | 70 | Cloudy |

| 2024-01-06 | NaN | 71 | Rainy |

| 2024-01-07 | 26.0 | 73 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-08 | 27.0 | 75 | Cloudy |

| 2024-01-09 | 28.0 | 76 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-10 | NaN | 78 | Rainy |

| 2024-01-11 | 30.0 | 79 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-12 | NaN | 80 | Cloudy |

| 2024-01-13 | 21.0 | 65 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-14 | 22.0 | 67 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-15 | 23.0 | 69 | Cloudy |

| 2024-01-16 | 24.0 | 70 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-17 | 25.0 | 71 | Cloudy |

| 2024-01-18 | NaN | 73 | Rainy |

| 2024-01-19 | 27.0 | 74 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-20 | NaN | 75 | Cloudy |

| 2024-01-21 | 28.0 | 76 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-22 | NaN | 77 | Rainy |

| 2024-01-23 | 30.0 | 78 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-24 | 31.0 | 79 | Cloudy |

| 2024-01-25 | 32.0 | 80 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-26 | NaN | 81 | Rainy |

| 2024-01-27 | 34.0 | 82 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-28 | NaN | 83 | Cloudy |

| 2024-01-29 | 35.0 | 84 | Sunny |

| 2024-01-30 | NaN | 85 | Rainy |

Utilizing MCARTest from [Schouten et al., 2022]:

Little's MCAR test p-value: 0.0000

Reject H₀: Strong evidence that data is NOT MCAR

A p-value of 0.0000 from Little’s MCAR test provides clear statistical evidence that the missing data in the dataset is not completely at random. This means that the pattern of missing values—in this case, temperature readings—is systematically related to other observed factors rather than occurring randomly throughout the dataset.

2.2.6. Chi-Square Test for MCAR Assessment in Time Series Data#

While Little’s MCAR test [Li, 2013, Little, 1988] remains the standard for comprehensive multivariate assessment of missing data patterns, the Chi-square test provides a focused approach to examine the relationship between missingness in a specific time series variable and categorical or time-based features. This method is particularly valuable for preliminary assessments and understanding localized missingness patterns.

Test Setup and Procedure

1. Create Missingness Indicator

Generate a binary variable (e.g., Variable_missing) where:

1= missing value in the target time series variable0= observed value

2. Select Comparative Variable

Choose an appropriate categorical or derived time-based feature from your dataset, such as:

Day of week

Month or season

Weather conditions

Equipment status categories

3. Construct Contingency Table

Create a cross-classification table showing the frequency distribution of observed versus missing values across categories of the comparative variable.

4. Execute Chi-Square Test of Independence

Apply the test with the following hypotheses:

H₀ (Null): Missingness is independent of the comparative variable (consistent with MCAR)

H₁ (Alternative): Missingness depends on the comparative variable (suggests non-MCAR)

5. Statistical Interpretation

p-value < α (typically 0.05): Reject H₀. Strong evidence that missingness is related to the comparative variable, indicating the data is likely not MCAR

p-value ≥ α: Fail to reject H₀. Insufficient evidence of dependency, consistent with MCAR for this specific relationship

Implementation:

Continuing with our weather data example:

=== MCAR Testing Results ===

Temperature vs. Weather Condition:

Chi-square: 20.0000, p-value: 0.0000

Reject the null hypothesis: Missingness in 'Temperature' is likely not MCAR in relation to 'Weather_Condition' (p-value=0.0000).

--------------------------------------------------

Temperature vs. Day of Week:

Chi-square: 2.5500, p-value: 0.8628

Do not reject the null hypothesis: Missingness in 'Temperature' is potentially MCAR in relation to 'DayOfWeek' (p-value=0.8628).

For our actual dataset, the Chi-square test for “Temperature vs. Weather Condition” yields a statistic of 20.0000 and a p-value of 0.0000, providing overwhelming evidence that missing temperature values are not randomly distributed across weather types. In our data, nearly every “Rainy” day is linked to a missing temperature, while “Sunny” days almost always have recorded temperatures, and “Cloudy” days are a mix but tend to have more observed values.

This clear pattern points to a strong relationship between adverse weather and missing temperature measurements. The missingness may stem from equipment malfunction during rain, intentional omission of data in challenging conditions, or other process issues associated with rainfall. A p-value this low means the connection between rain and missing temperatures is so pronounced that it cannot be attributed to random variation alone. In other words, on “Rainy” days, the likelihood of missing temperature records is exceptionally high, confirming that our data are not missing completely at random.

By contrast, for “Temperature vs. Day of Week,” the much higher p-value (0.8628) shows that missing temperature readings do not cluster on any particular day of the week. This lack of association indicates that, in our data, the time of the week does not influence whether a temperature is recorded or missing, so missingness is—by this measure—consistent with MCAR. This distinction demonstrates that while weather explains the missingness pattern, the day of the week does not in our dataset.

Your write-up is solid and provides clear, actionable information about the risks of simple methods and the advantages/limitations of advanced imputation strategies when MCAR is rejected. Here’s a revised, more concise version for greater clarity and flow, while retaining your key points and adding slight polish:

2.2.6.1. When MCAR Is Rejected (Non-Random Missingness)#

Risk Assessment:

Listwise deletion can introduce systematic bias by disproportionately removing certain observations, leading to incorrect conclusions about the underlying process.

Simple imputation methods (such as mean or median) ignore the reason for missingness, typically underestimate variance, and can distort variable relationships.

Results may be skewed toward specific conditions or time periods, resulting in inaccurate parameter estimates and potentially misleading findings.

Method |

When to Use |

Advantages |

Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

Multiple Imputation |

General use; assumes MAR |

Handles uncertainty in missing values, accurate estimates |

Computationally intensive; requires MAR, model spec |

Regression Imputation |

Predictors available; assumes MAR |

Leverages observed relationships |

May underestimate variability; assumes linearity |

Time Series Imputation |

Presence of temporal dependencies |

Utilizes sequence structure, well-suited for time series |

Each method has specific assumptions |

ARIMA-based Imputation |

Complex trends or seasonality |

Captures autocorrelation, trend, seasonality |

Requires correct model specification (p, d, q) |

Machine Learning Imputation |

Complex, nonlinear patterns |

Handles sophisticated relationships; can improve accuracy |

Risk of overfitting; needs careful validation |

Note: Overfitting—when an imputation model fits the idiosyncrasies of the training data but fails to generalize—should be guarded against, especially with machine learning methods.